Sitting nervously in an airport, Mahdi Jafargholizadeh had a hunch his getaway plan had been rumbled.

A karate champion in Iran, he had paid a smuggler to take him to Canada, but his journey ended at the boarding gate.

He was arrested in 2004 on suspicion of planning to be a spy for Israel, Iran’s arch-enemy.

The authorities in Iran heavily suppress freedom of expression, and crack down harshly on dissent. Even top athletes risk prosecution on what rights groups say are vague charges if they criticise authorities, as Mr Jafargholizadeh did.

For the next six months, Mr Jafargholizadeh alleges he was detained and tortured while interrogators pressured him to confess to bogus crimes.

Unwilling to cave, he was eventually released in 2005 and told there had been a mistake. He could compete in elite karate tournaments again, as if nothing had happened.

Except something had happened, something that had enhanced his desire to flee Iran for good.

His chance came in 2008, when he slipped away during a trip to Germany with the national team. From there, he claimed asylum in Finland, where he became a top coach.

Now, Mr Jafargholizadeh says he feels free.

The BBC put his allegations to Iranian authorities, which did not respond to requests for comment.

United for Navid

Alleging discrimination and political interference in sport, many Iranian athletes have fled abroad, including the three interviewed for this article.

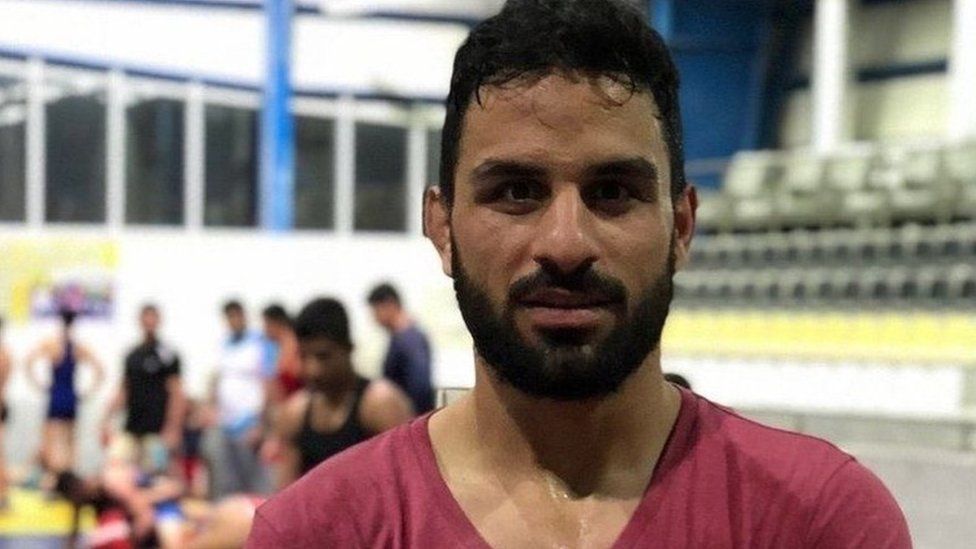

Each felt compelled to speak out following the execution of Iranian wrestler Navid Afkari in September 2020, which sparked international outcry.

Navid Afkari, 27, was sentenced to death after being convicted of the murder of a security guard during anti-government protests in 2018. He said he had been tortured into making a false confession.

His execution inspired United for Navid, a campaign that’s calling for Iran to be banned from international sporting events, including the upcoming Tokyo Olympics.

In recent months, the campaign has written three letters urging the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to investigate 20 cases of alleged athlete abuse in Iran.

When the BBC shared these cases with Iranian authorities, it received no reply.

The letter says these cases show Iran has breached the Olympic Charter, which commits organisers to “take action against any form of discrimination and violence in sport”.

The IOC told the BBC it was reviewing the allegations.

Should the IOC conclude that Iran has violated the Olympic Charter, an investigation would be opened to “fully establish the facts and take the necessary measures,” a spokesperson said.

Complaints of discrimination

Sardar Pashaei has been a leading voice in pressuring the IOC to do more.

He was a wrestling champion and national coach in Iran before he fled to the US in 2009.

He cited arbitrary travel bans, state surveillance and career obstruction as his reasons for leaving. He thinks his father’s political background probably had something to do with his treatment.

As a coach, he said his best wrestler was ordered to lose a match to avoid facing an Israeli competitor in the next round. Iran does not recognise Israel’s right to exist and forbids its athletes from competing against Israelis.

For female athletes, there are even more restrictions to consider.

For decades, Soheila Farahani was a successful volleyball player and referee at a national level in Iran. At 32, she broke gender barriers to become the first ever international female volleyball referee from the country.

In the glare of the public eye, her sexuality came under scrutiny.

“It was so difficult to figure out and I couldn’t talk with anyone,” she said, her voice cracking with emotion. “If you’re a lesbian in Iran, you’re at risk.”

As prying questions increased that risk, she emigrated to the US in 2015. Still, that didn’t exempt her from the Islamic Republic’s laws.

In 2018, she was expelled from the list of Iran’s international volleyball referees for not wearing the hijab (head covering) in the US. Wearing the hijab is compulsory for women in Iran, while same-sex relations are considered a crime punishable by death.

‘Sport is a threat to the government’

Another exiled female athlete was so fearful for her family’s safety in Iran, she declined to be named in this article. Since joining United for Navid, the threats have intensified, she said.

Most of them are Instagram messages, but some are SMS texts she believes were sent by members of Iran’s intelligence services.

One message, translated from Persian, read: “We will cut off your head and send it to your family if you continue your activities against us.”

The US-based Iranian journalist and human rights activist Masih Alinejad told the BBC threats against self-exiled athletes were typical.

“Sport is an opportunity for the Iranian government to write its own ideology on the bodies of the athletes,” she said.

But UK-based international affairs analyst Majid Tafreshi said United for Navid’s demands are detrimental to Iranian people and their national interests.

“Iranians do not support Afkari’s execution,” he said. “But almost everybody is absolutely against banning Iran from international sport.”

Short of a ban, Sardar Pashaei expects Olympic officials to at least investigate the discrimination and violence Iran has been accused of. Until they do, “we’re not going to give up”, he promised.

Source: BBC